Regarding that lab notebook… (Part 2: Is there a better way?)

Published:

Searching, searching, for a better receptacle.

Curious about better notebook options and what other scientists are using, first I asked around my computational group colleagues. They generally do not use any specialised ELN either, but the usual OneNote, gDoc, pen and paper, and the likes.

Turning my queries online, I found this paper in PLoS Computational Biology <Ten Simple Rules for a Computational Biologist’s Laboratory Notebook>. Although it is more about how to document rather than what to use to document, it is helpful for oneself to identify what a lab notebook is to them. For example, do you regard your notebook to be a legal record? (You should, by the way, according to the paper). Do you want your notebook to be accessible to anyone in the world? (See open-notebook science). Another related paper you may want to check out, regarding folder structure: <A Quick Guide to Organizing Computational Biology Projects>.

I also came across this Nature article <How to pick an electronic laboratory notebook>, which from the get-go already assumes that traditional notebook is cumbersome and electronic lab notebook (ELN) is definitely the future, but there are so many ELN options – how to choose? (If you are interested, one of the references has a comprehensive list.)

I looked at the options mentioned in the article and well, I don’t know, somehow I am turned off by all the commercial options. I think the ideal ELN for science should be open-source like Jupyter notebook.

One workflow from the article resonates with me, though –

Every month, his team exports pages to PDF files and signs them electronically; the files are then moved to a directory where they cannot be changed.

I like it because it lets people to use any form of notebook they want (even pen and paper!), as long as it is exportable to PDF, and at the same time fulfilling audit requirement of timestamping and non-editability.

Version control as timestamping and more

I would submit that a better (but not necessarily easier) way to do this is to borrow a concept from software development, version control. In software development, the version control software keeps track of the source code of the project. It is a sort of more sophisticated version of Word’s track changes feature.

Another thing that we should get into version control...

Image credit: PHDComics

In our case, our notebook is the source code. Indeed, there are others who have the same idea. Googling ‘git lab notebook’ gives several hits, for example this one is centred around the calendar days and lives in GitHub. (The version control software that I am familiar with is git, so I will mention git a lot.)

I shall attempt to describe the git version control workflow: You work on a project which has features A and B; you stage the changes related to feature A and commit, thus timestamping and logging it in the timeline; you do the same for feature B. Staging is precisely for this purpose, to bundle together changes in a logically-structured manner. The version control software only saves the changed files (git saves the whole file, other softwares may save only the difference), so this is a good thing, storage-wise.

In this way you would accumulate a linear collections of timepoint snapshots (branching in the timeline is possible but let’s exclude it for simplicity), in which you have a record of every change in your notebook (isn’t this like… blockchain?). Even if you go back and revert some changes you make because of a mistake for instance, that is recorded as yet another commit.

Sounds arcane? Probably to the typical (non-computational) scientists, all this sounds cumbersome to learn and get into. Even for me, typing all those obscure git commands to the terminal take sometime to get used to.

Ideally, they (I’m not sure who… kind strangers?) should make git version control more user-friendly and simpler for the user (nice GUI; and we can also skip the staging for example) and for the auditor (they can see the whole timeline and there is a slider button to quickly review all changes), and I think many would gladly use it. The weakness of this approach is, the ELN needs to be largely plain text (just like a software source code), otherwise the changes between commits may be difficult to view.

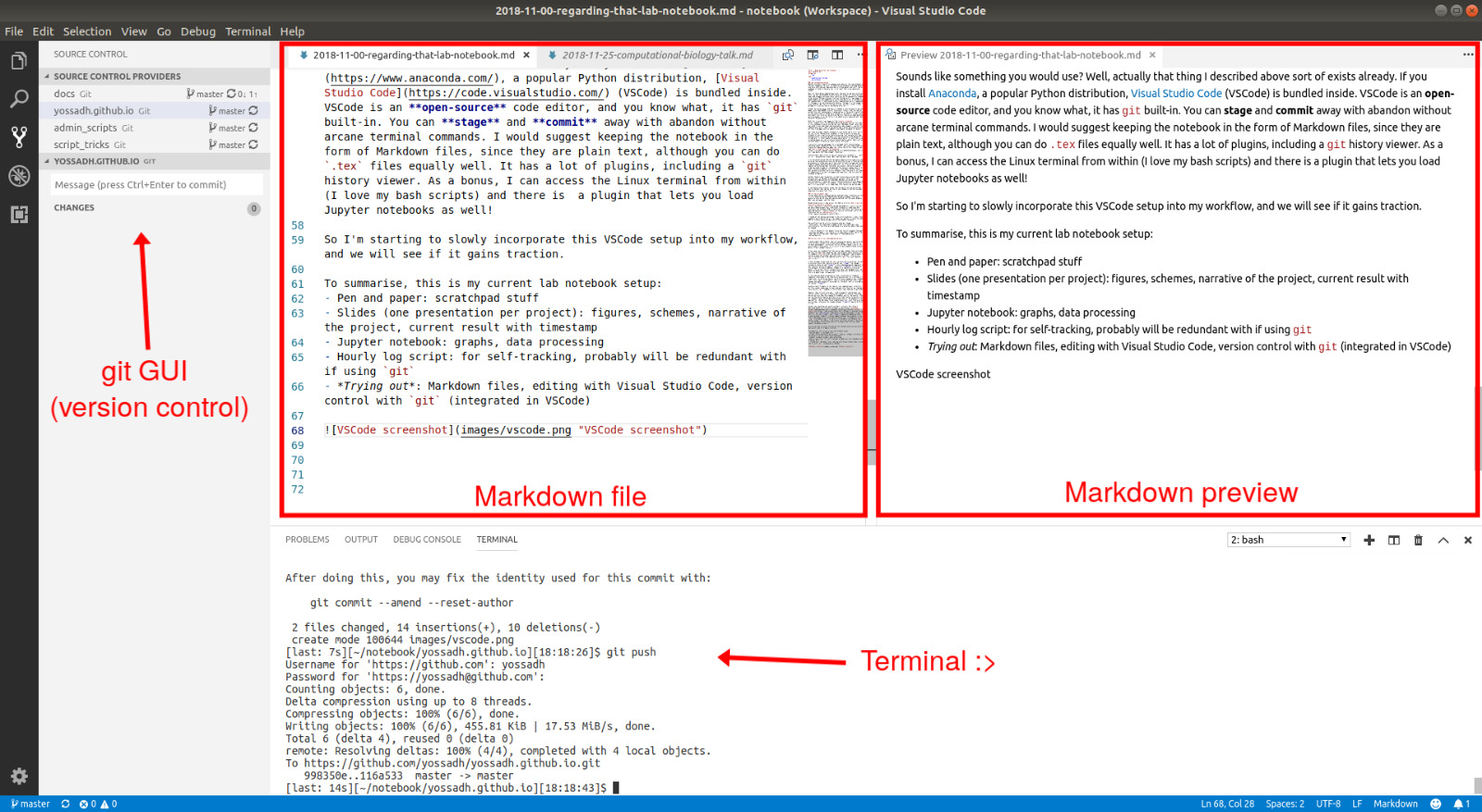

Sounds like something you would use? Well, actually that thing I described above sort of exists already. If you install Anaconda, a popular Python distribution, Visual Studio Code (VSCode) is bundled inside. VSCode is an open-source code editor, and you know what, it has git built-in. You can stage and commit away with abandon without arcane terminal commands. I would suggest keeping the notebook in the form of Markdown files, since they are plain text, although you can do .tex files equally well. It has a lot of plugins, including a git history viewer. As a bonus, I can access the Linux terminal from within (I love my bash scripts) and there is a plugin that lets you load Jupyter notebooks as well!

You can see my VSCode setup in the screenshot below:

Take a closer look at the Markdown file in the screenshot… Yup, this blogpost itself is written with VSCode. Quite meta, isn’t it?

So I’m starting to slowly incorporate this VSCode setup into my workflow, and we will see if it gains traction.

To summarise, this is my current lab notebook setup:

- Pen and paper: scratchpad stuff

- Slides (one presentation per project): figures, schemes, narrative of the project, current result with timestamp

- Jupyter notebook: graphs, data processing

- Hourly log script: for self-tracking, probably will be redundant if using

git - Trying out: Markdown files, editing with Visual Studio Code, version control with

git(integrated in VSCode)

Actually, even after brain-dumping all this notebooking stuff, I’m still a bit fuzzy about the concept. I guess, for now, my lab notebook philosophy is: track as much as possible, with least effort possible.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *